How to become a copyeditor

✻ By Sharon Lapkin

If you’re wondering about how to become a copyeditor, there are a few important things to know. You need a razor sharp eye and an ability to focus on consistency from the beginning to end of a document or manuscript.

It’s an exciting career if you love writing (especially other people’s writing).

You need to love it so much that you’re happy to spend your days correcting grammar, syntax and structure. Even if that means you sometimes have to justify those corrections to the writer.

There are many different types of editors, but there are common characteristics shared by all of them. Or, we might start off as one type of editor and end up another.

Copyeditors have a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the following editorial skills:

Good grammar and punctuation

Tone and voice

Copyright

Author–editor relationships

Legal and ethical issues

Word styles, track changes, formatting

Grammar rules

Good sentence and paragraph structure

Fact-checking skills

Editorial mark-up

Cultural sensitivity

Discriminatory language

In my editorial career, I worked as a subeditor, copyeditor, senior editor, coordinating editor, project editor, developmental editor, supervising editor and managing editor.

This provided me with a broad base of knowledge and experience across all aspects of the editorial process.

What does an copyeditor do?

Let’s focus on how to become a copywriter, which is the most popular type of editor.

Copyeditors edit a page line by line for sense, formatting, grammar and punctuation.

They also align the text on the page with the agreed editorial style. This is generally the house style or, if there isn’t a house style, they might rely on the Australian Government Style Manual or the Chicago Manual of Style.

When a document requires more than a line-by-line edit, we call this a structural edit.

Then the copyeditor digs deeper and edits for meaning, flow and sense. They may go back to the client and suggest that particular sentences or paragraphs be moved or rewritten, or they may have questions about the tone or accuracy of the text.

Copyeditors review and correct content in all types of projects. You can find them working on projects such as newspaper and book articles, annual reports, white papers, website content and book manuscripts.

Do you still want to learn how to become a copywriter? Great! Let’s keep going.

The home of professional editors

Most professional editors in Australia belong to the Institute of Professional Editors (IPEd).

Editors in other countries have their own organisations, and these are important because they oversee and maintain editorial standards.

Editors must satisfy formal entry requirements and work as a professional editor to qualify for IPEd membership.

When hiring a copyeditor, make sure they’re a professional member of this industry organisation.

Good copyeditors develop close working relationships with their authors and clients. They consult with them about any intended changes beyond grammar and punctuation.

If they don’t have direct access to the writer, then they’ll be working from an editorial brief.

What does a copyeditor do about legal and ethical issues? The Australian Standards for Editing Practice defines the core standards that professional editors should meet.

These standards set out the knowledge and skills for good editorial practice, including legal and ethical obligations, as well as substance and structural tasks.

What does a proofreader do?

If you want to know how to become a copyeditor then, by default, you’ll learn how to be a proofreader.

Proofreading is the final task in the editorial process.

The proofreader should be the last person to make changes to the content.

Their role is to check the text for typos, grammatical errors, punctuation, page numbers and editorial style.

They’ll also check captions, images, headings and the table of content.

Proofreaders focus on those things that might be overlooked by the writer and copyeditor before them.

Outside traditional publishing, people often don’t differentiate between copyediting and proofreading.

But to a copyeditor and proofreader they’re two distinct processes. This is why it’s important to establish exactly what’s needed before employing a copyeditor.

Legal and ethical matters

Copyeditors are trained to recognise content that appears to be written by a person who’s not the writer they’re working with.

We spot the change of voice in the text. To us, it’s like finding an avocado in a banana smoothie.

Often people don’t realise they’re plagiarising and, once it’s pointed out, it’s a quick and easy fix.

We can look into obtaining permission to republish content if it’s intrinsic to the project.

Or we might summarise or paraphrase text from other sources while always acknowledging the original source.

Applying for copyright permission is usually a straightforward process. People are often flattered that you want to use their content.

It’s also good manners to acknowledge content created by somebody else. Think about using a backlink if you can. This helps their SEO as well as yours.

Permission may not always be needed, but acknowledgement is always required. If you want to use content from another source, check their terms and conditions on their website first.

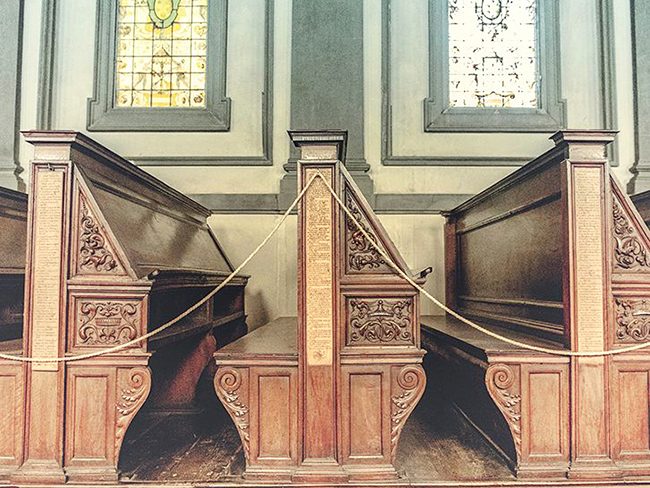

A website’s terms and conditions are generally located at the bottom of their homepage (left).

Cultural sensitivity and discriminatory language

Take care not to convey explicit or implicit judgements about other people’s cultural differences.

Context is important when looking at this type of content and common sense is paramount.

What does a copyeditor do about offensive content? They’ll alert the writer to the problem. If they’ve worked in-house, they’ll generally know a lawyer, or somebody with legal training, who can provide an informed opinion.

Keep an eye out because discriminatory language or meaning can appear in content unintentionally.

References to age, gender, ethnicity, sexual preference, accent or disability that are not relevant to the story can be examples of discriminatory language.

Good copyeditors identify any issues they encounter and suggest alternative text.

Design and formatting

Copyeditors who have worked in publishing environments are used to marking up corrections for graphic designers.

We don’t design pages, but we do look at all the text-based elements on a page and identify any parts of it that aren’t working optimally.

Copyeditors and designers work together to create high-quality content. They go back and forth marking up the content and taking in the corrections until the page is perfect.

The relationship between the copyeditor and the designer is essential to the quality of the work.

How to develop an editorial mindset

When I was a trainee editor, I’d imagine that a page in a book I was working on was a room in a house.

The headings, graphics, images and all the other elements on the page were furniture in the room.

These elements had to come together in a cohesive, aesthetic way for the page to function.

The design had to support the text and not inhibit or misrepresent its meaning.

Editors call this process ‘page-fitting’, but the house idea worked for me.

Still want to know how to become a copyditor? Yay! Good to hear it.

Can you really rely on a spellchecker?

Spellcheckers regularly get things wrong.

To start with, you may be checking UK (Australian) English through a US spellchecker.

So the Australian spelling ‘specialisation’ will be marked up as an error because the spellchecker thinks it should be the US spelling ‘specialization’.

Spellcheckers check if words are spelled correctly, not whether they’re used correctly.

So a sentence such as ‘Witch one was rite?’ could be assessed as correct.

Similarly, homophones are troublesome for spellcheckers. So ‘heir’ and ‘air’ could be substituted and missed. So could ‘bare’ and ‘bear’.

According to Oxford Dictionaries, a spellchecker might not know the difference between ‘socialite’ and ‘socialist’, or ‘definitely’ and ‘defiantly’. It may also confuse ‘public’ with ‘pubic’. That could be embarrassing!

Grammar and punctuation

When subject matter experts write, they focus on the meaning and structure of the content, not relative pronouns, commas or other constructions.

It’s difficult to explain complex concepts or review academic research while trying to be word perfect. In these situations, an editor is a writer’s best friend.

A good writer–editor relationship is invaluable, and copyeditors are trained to use a friendly tone when marking up corrections.

Have you noticed how best-selling authors often talk about their editors in affectionate terms? That’s because they understand each other and are, pun intended, always on the same page.

Grammar evolves and editors keep up with changes

What does a copyeditor do about grammar that’s continually evolving?

With every new edition of a dictionary words become extinct and new words are invented. These new words, called neologisms, can be challenging to keep up with. Lucky that editors, in general, love words.

Words start being used as compounds (e.g. well-being) and hyphens are inserted between them. Then compounds lose their hyphens (e.g. wellbeing) and become singular words. An editor keeps track of all these evolutionary changes.

It’s a big job knowing a dictionary back to front, but an editor will generally know common usage without referring to the dictionary. They probably even have a shortcut on their screen to locate a current usage within a minute.

An editor will know when to use ‘which’ and ‘that’ and you’ll find this knowledge is the difference between amateur and professional content.

Some people avoid punctuation because they’d rather have an absence of it than an error. If that’s you, consider this sentence:

“Let’s eat Evelyn,” versus “Let’s eat, Evelyn.”

If you want to be clearly understood there’s no way around it. You have to learn punctuation rules or hire an editor.

Why you should worry about editorial style

When you’re learning how to become a copyeditor, always remember that editorial style ensures consistency.

Suppose a medical college uses upper case ‘C’ in ‘College’ in all instances. That style needs to be consistent throughout the College’s content or its readers may become distracted.

It’s also about saying the same thing in the same way throughout a document. For example, Jacaranda University shouldn’t be shortened to ‘Jacaranda uni’ in the same piece of content.

You wouldn’t use ‘and’ and an ampersand ‘&’ in the same document (unless it were in a company name). You’d also punctuate lists in the same way throughout a project.

Consistency is important because it builds reader confidence and reduces distractions in the text.

It demonstrates clearly that the content has been created by professionals, which is exactly what you want. Readers will find it difficult to trust content that’s plagued by errors and inconsistencies.

Even if writers are highly qualified in their field, errors can devalue their authority and make them look less professional.

A good style guide clearly defines an organisation’s tone and voice. It lets us know the differences between the brand’s usage and common usage.

The style guide also lists those instances where the organisation might divert from popular usage, such as the upper-case ‘C’ in College.

Your list of good editorial style guides

The Australian Government Style Manual was recently updated and is essential for anybody writing or editing Australian Government content.

The Melbourne University Law Review publishes the Australian Guide to Legal Citation and it’s free to download.

APA (American Psychological Association) Style is used by many academic and professional organisations. Explore it here.

The ABC Style Guide is extensive and available to the public.

For guidance on Indigenous terminology, you might like Textshop’s Guide to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander terminology.

Learning how to become a copyeditor is a serious career decision. It involves lifelong learning as editorial standards are always evolving and good writing requires consistency.

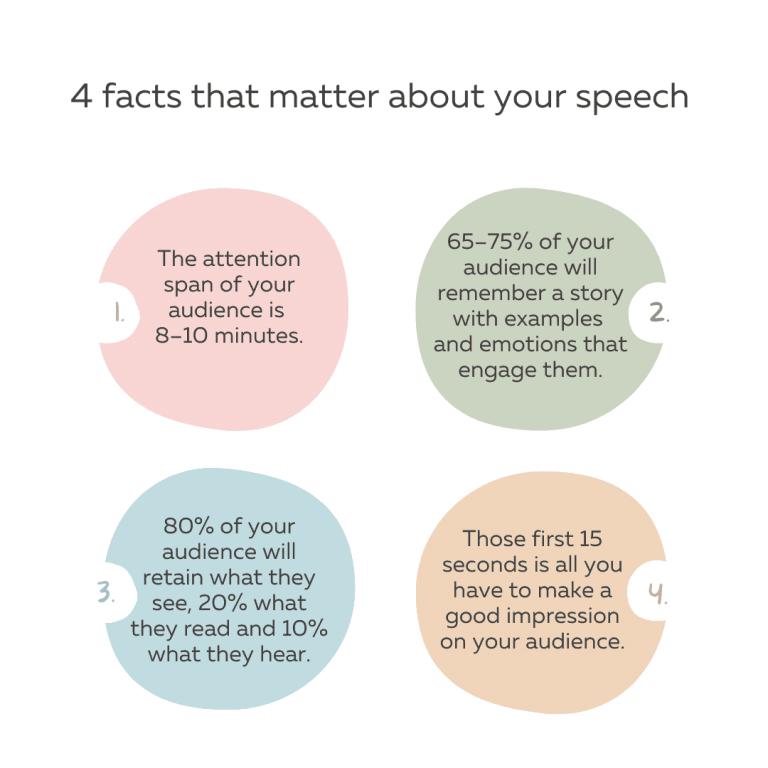

We might be applying house rules and styles to writing, but we’re also working from the perspective of the reader and analysing how they’ll approach and process the text we’re editing.

The important thing to remember is that any type of editing is a journey. You never know it all – even when you become an expert.

About Sharon Lapkin

Sharon is a content writer and award-winning editor. After acquiring two masters degrees (one in education and one in editing and comms) she worked in the publishing industry for more than 12 years. A number of major publishing accomplishments came her way, including the eighth edition of Cookery the Australian Way (more than a million copies sold across its eight editions), before she moved into corporate publishing.

Sharon worked in senior roles in medical colleges and educational organisations until 2017. Then she left her role as editorial services manager for the corporate arm of a university and founded Textshop Content – a content writing and copyediting agency that provides services to Australia’s leading universities and companies.

Lastly, consider context when you add your keyword into the alt text. Adding random keywords may cause your site to be seen as spam.

Lastly, consider context when you add your keyword into the alt text. Adding random keywords may cause your site to be seen as spam.