The difference between paraphrasing and summarising

✻ By Sharon Lapkin

We’ve all felt it.

That YES moment when you find the right text to support what you’re trying to say.

But how can you use another person’s written words while respecting their intellectual property rights?

What are the rules that govern how to quote, paraphrase or summarise somebody else’s writing?

To answer these questions, and know the difference between paraphrasing and summarising, we need to look briefly at quoting, copyright and ‘fair use’.

What does copyright mean?

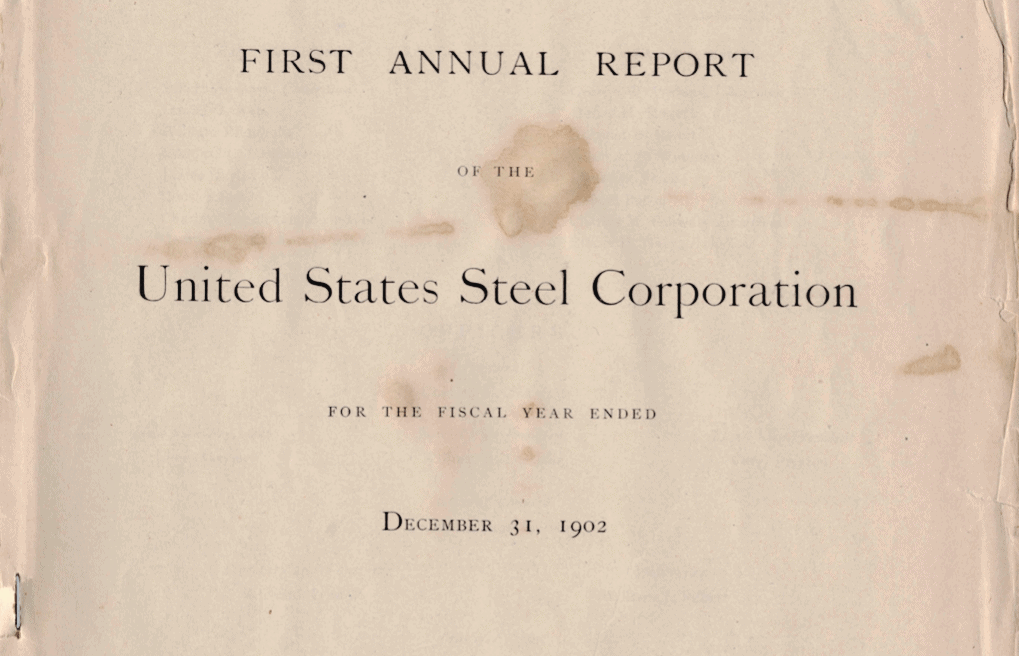

Copyright grants legal protection of your work and prohibits other people copying and republishing it as their own.

It protects the rights of authors, writers, photographers, painters, song writers and others who create intellectual property.

You don’t need to apply for copyright. It’s automatically granted to you as the creator of literary work (yes, even business writing).

The copyright symbol © is a good reminder to an audience that what they’re reading is under copyright. However, the symbol is not mandatory. The writing is under copyright even if the © is missing in action.

It’s important to remember that you can’t copyright ideas, only the way those ideas are expressed.

Can I copy content under the 'fair dealing' provision?

In Australia, you can copy up to 10% of publications such as a chapter, an article, a song or a poem.

In an online publication, you can copy up to 10% of the total word count of an online article, chapter or blog post.

The Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) also allows the fair use provision for:

– research or study

– criticism or review

– parody and satire, and news reporting

– judicial proceedings or professional advice.

A couple of points to remember:

Fair use requires author attribution. You must provide author details and a link to the publication.

If you need to reproduce more than 10%, you must seek permission from the copyright holder (usually the author.)

Don’t be alarmed about seeking permission. It’s often as easy as writing an email. People are usually grateful that you asked!

Keep a record of your correspondence with the copyright holder, including when they consented to your use of their content.

Rule #1: Always accredit the writer

The most important principle you must observe to protect your professional integrity and avoid legal liability is the rule of attribution.

A person’s creative work is their intellectual property and you should NEVER use it without attributing them as the rightful owner of that content.

The last thing you want is to be accused of plagiarism or copyright infringement – although fear is not the reason we respect the work of other writers.

Keep reading because I’ll explain in this blog post how you can utilise someone else’s text and stay on the right side of the Copyright Act.

How to quote correctly

A quote is a reproduction of a written or oral statement made by others.

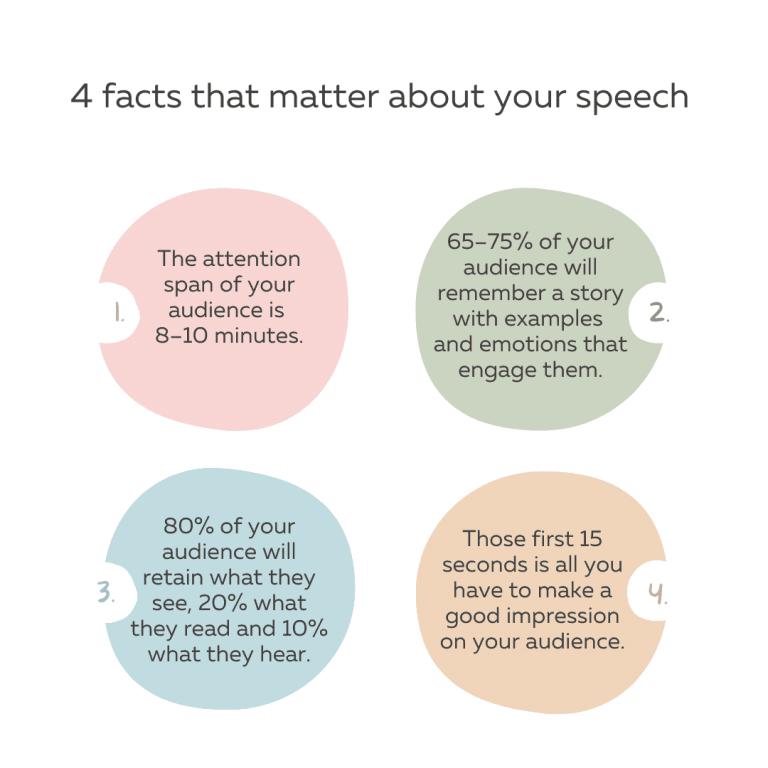

It’s essential that all quotes are exactly the same as the original. That’s right – 100% word-for-word.

If there’s an error or a typo, leave it and insert [sic] after it, which is Latin for ‘thus’ or ‘so’.

The difference between paraphrasing and summarising is worth noting here. You’re more likely to use short or part quotes in paraphrasing than summarising.

Quotations can be divided into two categories – short quotes and long quotes (also known as block quotes).

Short quotes

A short quote consists of fewer than 30 words.

Short quotes are marked by single or double quotation marks.

Double quote marks are used for dialogue (people speaking), and single quote marks are used for quoting from secondary sources (such as a newspaper or YouTube). Some writers and editors use single quote marks for emphasis.

In Australia, full stops, commas, question marks and exclamation marks should be placed within the final quotation if they appear as part of the text.

Example

‘Have you found my book?’ he asked.

If the punctuation mark is part of the sentence outside the quoted text, it should be placed outside the closing quotation mark.

Example

Did your manager instruct you to ‘complete the job’?

Quotes must always be accompanied by a source citation, also known as a source line.

If you’re using a quote that’s not the writer’s work, but a quote from another publication, try to find the original work and quote from that publication (the original source). If you can’t find the original source present the quote in a similar way to the following:

Example

Joanna Fellows wrote about President Obama’s speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention, when he said ‘Do we participate in the politics of cynicism or do we participate in the politics of hope?’

Keep these principles in mind as you use short quotes:

– The quote is short and is usually integrated within the sentence where it appears.

– Check your house style guide for citation policy.

– House styles can include citation references in the body of the text while others use EndNote or footnotes.

– If the content with the quote is being published online, include a link to the original source.

Long (or block) quotes

Longer quotes that include more than 30 words should appear as indented blocks of text without quote marks.

Depending on house style, the font size of the block quote can be either the same size as the body text in the rest of the article, or one size smaller.

Note, a long quote doesn’t have quote marks if it’s indented. But, if you’re indenting a quote, ensure you indent it on both sides.

Keep these principles in mind as you use long quotes:

– Include some text to introduce the block quote in its proper context.

– The sentence immediately before the quote can end in a colon, comma or nothing at all.

– Indent the block quote on both sides.

– Use single spacing in the body of the block quote.

– Often the block quote will appear in font that is one size smaller than the body text of your article.

– Don’t use quotation marks.

– In academic writing, house styles can include citation references in the body of the text while others use end notes or footnotes.

How to paraphrase like an expert

Think of a paraphrase as a translation or restatement of a piece of writing by another writer.

When paraphrasing, you’re using your own words to convey the original meaning of another writer.

This restatement is rendered to clarify or explain another writer’s work, to reproduce another writer’s ideas within your own writing, or to avoid copying another writer’s work (plagiarism).

A synonym finder is an essential tool when paraphrasing. I use Word hippo and highly recommend it.

By contrast, a summary is a precise compendium of the facts without fluff or fancy talk.

A paraphrase and a summary will both be shorter than the source text and must credit the original author.

Following is an excerpt from one of my blog posts. It’s been on page one of Google for the past two years, both as a featured snippet and in #1 position.

Compare this to the summary (further down) where I use the same blog post to demonstrate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising.

Original blog excerpt for paraphrasing

In the early 1600s, when the Bibliotheca Angelica in Rome opened its doors, books were generally kept under lock and key, or in chained libraries – such as the 15th-century Bibliotheca Malatestianain Cesena and the Hereford Cathedral Library in England.

It took thousands of hours of painstaking work to make a book – copying text by hand, adding decorative elements, illustrations, page numbers and indexes before binding the pages together and adding a cover.

This made books expensive and valuable items. Medieval books sometimes had ‘book curses’ placed at the front, warning people that if they stole or defaced the book they would be cursed.

But, in a revolutionary step, the Angelica opened its door to all people with no class distinctions or government restrictions.

All they needed to access this remarkable collection of volumes, rare maps and other material was a curious mind, a yearning to read and a thirst for knowledge.

It was a momentous decision to grant ordinary people access to scholarly knowledge.

Looking back we can see that Bibliotheca Angelica and other early public libraries, such as the Milan’s Bibliotheca Ambrosiana, helped bring about the democratisation of education when, rather surprisingly, ordinary people were free to embrace the archives of history and knowledge.

Even for somebody accustomed to Rome’s ancient piazzas and cobblestone alleyways, it’s easy to get lost searching for the Bibliotheca Angelica.

The library’s humble street presence belies its pre-eminence as Rome’s oldest public library – and one of the first public libraries in the world.

The entrance to the library provides no indication of its historical significance or the treasures within it.

Like the adjacent Basilica di Sant’Agostino, which is home to works by Caravaggio, Raphael and Sansovino, its riches are cloaked by a plain unassuming exterior.

Completed paraphrase of blog excerpt

The democratisation of knowledge in Europe over the 16th and 17th centuries occurred because the advent of printing press technology allowed books to be mass produced for broad public consumption.

The establishment of public libraries was one manifestation of this process. Writing for her Textshop website, Sharon Lapkin describes the first of those public libraries, Rome’s Biblioteca Angelica, that opened its doors in 1609.

She extols the ‘remarkable collection of volumes, rare maps and other material’ concealed behind the library’s unassuming façade in a Roman side street.

For the first time in human history, the average Roman citizen was able to access independent sources of information rather than rely on the oral narratives spoken by others.

Keep these principles in mind when paraphrasing:

– Make sure your rewritten words accurately express the ideas of the content you’re paraphrasing.

– While changing the sentence structure and wording, you should include any specific terms that are relevant to the meaning of the segment. For example, ‘consumer prices’ or ‘inflation’ are difficult to replace with similar words.

– Always include a source line and/or link so your readers can access the original writer’s work.

– If using three words or more in a row from the original work enclose them in quotation marks.

How to summarise like an expert

The simplest way to reference the ideas of other writers is through a summary.

A summary is a roundup of someone else’s written work. By definition, your summary will be shorter than the original work, although there are no hard-and-fast limits on length.

Your summary will include the main points of the original work, while discarding its unessential details.

While you credit the original author of the work, make sure your summary is written in your own words.

The difference between paraphrasing and summarising is that the former restates the writer’s ideas using synonyms and flair and the latter extracts the facts from the fluff.

Following is a summary of the same blog post excerpt that was used to demonstrate paraphrasing.

This summary should help you see the difference between paraphrasing and summarising.

Completed summary of blog excerpt

In a blog post published on her Textshop website, Sharon Lapkin tells us the story of the Biblioteca Angelica, Europe’s first public library.

Prior to the early 17th century, the expense of hand-copying and illustrating books made them precious commodities that were kept under lock and key.

The opening of the Biblioteca Angelica to the public was part of the democratisation of knowledge that emerged during this period of history.

For the first time, average people could access books that previously were restricted to the select few.

The unassuming façade of the Biblioteca Angelica conceals a milestone in the evolution of human knowledge and education.

Keep these principles in mind as you write a summary:

– Make sure you include the main point(s) while omitting unnecessary details.

– Use your own words while crediting the author of the work you are summarising.

– Always include a source line and/or link so your readers can access the original writer’s work.

To paraphrase or to summarise?

Understanding the difference between paraphrasing and summarising is an essential skill for any writer.

Always read through the larger piece of writing before deciding whether to summarise or paraphrase.

Both provide the opportunity to reproduce the ideas, writing and thoughts of experts without the risk of plagiarism.