How to copyedit like an expert

✻ By Sharon Lapkin

Let me show you how to copyedit like an expert in 2022.

How to get your project ready to go in one efficient process.

I’m going to share a process with you that I developed after working for 14 years as a professional editor.

With this process, you’ll find and correct typos, grammar and punctuation errors, and you’ll identify inconsistencies and anything else that’s not right.

The secret formula: combining two tasks

To show you how to copyedit like an expert we’re going to combine editing and proofreading into one process.

Editing is often called copyediting, and it’s done after the writer has finished the writing. It requires a deep and meaningful look at the content, and includes checking sentence structure, grammar and punctuation. Depending on the type of edit, it may also include a copyright check, a fact-check and marking up any design errors.

Proofreading is completed after the edit. It’s the last stage of the editorial process and requires a comprehensive reading of the edited content. No small details should be left out. Proofing also includes checking any headings, page numbers, URLs, captions and, most importantly, signing off the project.

Getting started – the essential checklist

The checklist is our most important tool and it’s best to create it manually – especially if you’re editing onscreen.

All you’ll need is a notepad and pen.

You’re going to write a list of words and terms as you edit onscreen. At the same time, you’ll add things you’ll come back and resolve after the edit.

The reason you’re writing things up in the checklist to resolve later is that sometimes an issue you spot during the first read resolves itself later in the text.

Divide the task in two

Next step is to divide the process in two.

The first stage is the edit (the first read), and the second is working through the checklist (the second read).

There’s one important thing to remember.

You can’t do a good job in the second read, unless you create a very good checklist during your edit (first read).

So take time in your edit to note down anything that isn’t consistent or that lacks clarity.

The tools you need

Other tools are needed if you’re going to conduct a quality edit.

Have your dictionary on a short cut on your desktop, and make sure it’s one that uses local spellings.

In Australia we use UK spellings and the reference used by publishing professionals is the Macquarie Dictionary.

Synonym finders such as Related Words and Thesaurus.com can also be found online and it’s a good idea to have a short cut to one of those as well.

When a word is overused, copy it into a good synonym finder, locate a word that means the same thing and substitute it to avoid repetition.

Find the editorial house style guide

Find out if there’s an editorial style guide that applies to what you’re editing.

A style guide can range from a few pages to 25 or more pages in length.

If you’re writing for a company, ask them if they have a style guide.

It will contain the preferred spellings and expressions they use. This is especially important for things like lists and capitalisation.

I always read a client’s style guide before commencing an edit and then refer back to it throughout the process. Every company has its editorial idiosyncrasies and it’s best to know these upfront.

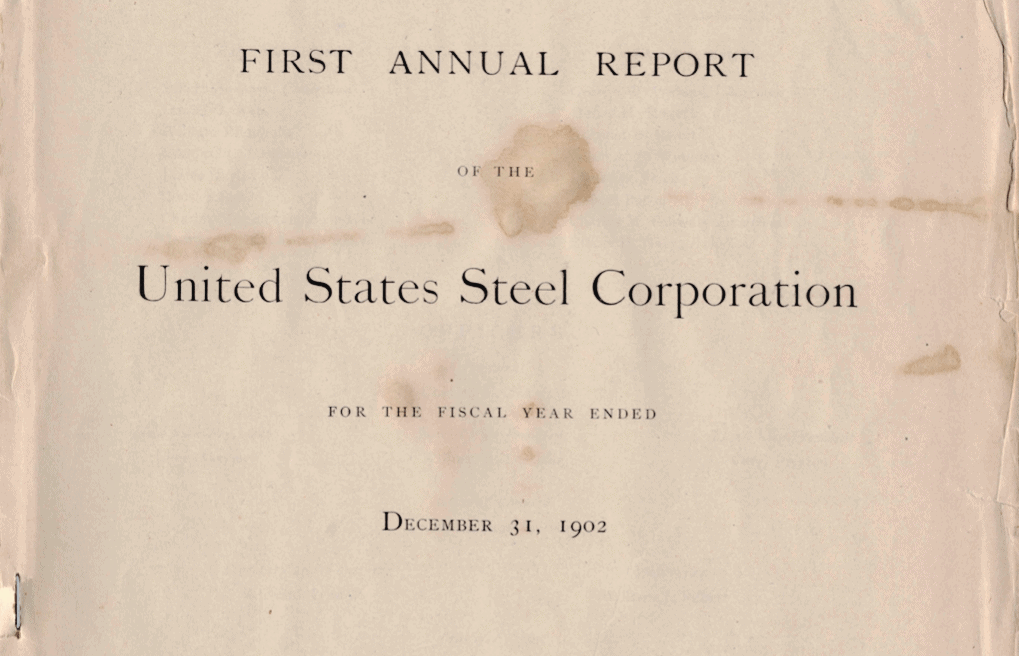

Often the client will ask you to use a commercial style guide such as the Chicago Manual of Style or, if you’re in Australia, the Government Style Manual. This gives you a reference point for your edit.

It’s a good idea to keep your level of interference in check when you’re editing somebody else’s writing.

Take care not to change the meaning of anything the writer has written and, if in doubt, add a comment or question for the writer rather than arbitrarily change something.

Work through the edit systematically and add any issues, such as those mentioned below, to your checklist.

It’s better to include more items in your checklist, than have a query in your second read of the document that wasn’t noted in your checklist during your first read.

As you work through the document write all the abbreviations and acronyms used by the writer in your checklist.

EXAMPLE – Notice of Meeting (NOM), Annual General Meeting (AGM), Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), Australian Taxation Office (ATO)

Write down any words that are used in unique or unusual ways.

EXAMPLE – World Health Organization (WHO) – note I’m adding this because we’re retaining the US spelling. (Usually we’d change it to ‘organisation’.) Other examples might be unusual names such as Browne (Brown) and Marc (Mark), and any expressions used that differ from house style.

Capitalisation is not always straightforward.

Organisations may differ in their preferences for what is upper case and what is lower case.

EXAMPLE – Universities often upper case ‘U’ when writing ‘University’ and medical colleges generally upper case ‘C’ in College.

Write idiosyncrasies like this in your checklist as you edit.

If you come across anything troubling that you can’t resolve without further research note it in your checklist, but also highlight it on your screen or draw a circle around it in pencil in the document.

Remember, the answer to your query may reveal itself as you work through your edit. If not, you have it noted to come back to in your second read.

How are you going? Keep reading and I’ll show you how to copyedit like an expert.

In any edit, you’re looking for more than typos.

You’re reading for idea or word repetition, lack of clarity, poorly structured sentences, and grammar and punctuation errors.

Here are some of the things you need to check for and correct as you edit.

US spelling in Australian writing

EXAMPLE – organization, color, licence and journaling.

Change these to organisation, colour, license (verb, or licence – noun) and journalling.

Using the same words over and over

Spot the problem here:

We couldn’t wait to visit the markets in Tuscany, where we hoped to find fresh ripe tomatoes and fresh ripe peaches.

Let’s fix it by consulting our synonym finder.

We couldn’t wait to visit the markets in Tuscany, where we hoped to find fresh ripe tomatoes and juicy peaches.

Inconsistency of terms

For abbreviations and acronyms we spell them out in the first instance and then use the shortened form from that point on.

EXAMPLE – the Australian Tax Office (ATO) is busy doing tax returns this time of year, so when I phoned the ATO they placed me in a queue.

In longer documents this practice can get messy and that’s why we note it in our checklist.

Acronyms and abbreviations

For abbreviations and acronyms we spell them out in the first instance and then use the shortened form from that point on.

EXAMPLE – the Australian Tax Office (ATO) is busy doing tax returns this time of year, so when I phoned the ATO they placed me in a queue.

In longer documents this practice can get messy and that’s why we note it in our checklist.

Don't forget the punctuation

As you copyedit, check for misplaced commas, semi-colons and sentences that are too long.

Check more than words

Check the spaces between paragraphs are even.

Do tables, photos and illustrations have captions?

Are all the links working?

Do you know how to copyedit like an expert yet?

The second read

After you’ve edited the document, you should have a comprehensive checklist of items to take into your second read.

To complete the process, you’re going to work through the content again, but this time with your checklist.

For an optimal result your edited text should be in Word or PDF format.

In the second read you must do the checklist work manually.

NEVER use 'Change all'

Seriously, no matter how short on time you are, don’t use the function on your keyboard that supposedly corrects every example of the error.

It will quite possibly insert multiple errors into your document because it will misinterpret closely aligned words.

To check abbreviations and acronyms, work through the items one at a time using the ‘Search’ function on your computer. It should be in the top right-hand corner of your screen.

Let’s say you’re checking that the Australian Taxation Office is spelled out in the first instance and the acronym (ATO) is used in every instance after that.

You’ll search throughout the document for ‘Australian Taxation Office’ and change all the long form usages to ‘ATO’ – except for the first instance, of course.

If you want to ensure ‘Browne’ is spelled correctly, you’ll search for the incorrect spelling – Brown.

To standardise capitalisation throughout the document, you should check every instance manually, unless you have a search function that will isolate upper case and lower case searches.

For example, if you’re checking that ‘University’ is upper case all the way through, type in ‘university’ and check every instance.

This might sound tedious, but you pick up speed and get through it quickly.

Use the search function to check for double spaces by hitting your space bar twice in the search bar.

Check commas are correctly spaced by hitting your space bar once followed by a comma.

Do the same to check for spaces before full stops.

You’ll find a vast array of things you can check using the search function, and the more you use it, the faster and more efficient you’ll be.

Copyedit like an expert – you've done it!

After checking and resolving every item on the checklist you should now have a well-edited document.

My checklist method enables the copyeditor to see the document with fresh eyes and to focus on the small, important details.

When a proofreader works through a document simply by reading it from beginning to end, they can miss errors in lengthy, dense or complex text. This process is the best way I know to conduct a comprehensive edit that picks up all the errors and inconsistencies.

It really is how to copyedit like an expert!

Before you go

Still want to learn how copyedit like an expert? You might also enjoy How to become a copyeditor.

Check you’re not making common mistakes in your writing in 9 common errors every writer should know about.

If you want to improve your blog writing take a look at How to write a smashing blog post.

About Sharon Lapkin

Sharon is a content writer and award-winning editor. After acquiring two masters degrees (one in education and one in editing and comms) she worked in the publishing industry for more than 12 years. A number of major publishing accomplishments came her way, including the eighth edition of Cookery the Australian Way (more than a million copies sold across its eight editions), before she moved into corporate publishing.

Sharon worked in senior roles in medical colleges and educational organisations until 2017. Then she left her role as editorial services manager for the corporate arm of a university and founded Textshop Content – a content writing and copyediting agency that provides services to Australia’s leading universities and companies.