The library Michelangelo designed

By Sharon Lapkin *

A few years ago, I attended a writing workshop in Florence’s historical district of San Niccolo. The location was perfect for exploring the quieter, non-touristy parts of Firenze.

The magnificent Bardini Gardens were nearby, and it was an exhilerating walk up the hill to Basilica San Miniato al Monte and Piazza Michelangelo.

One sun-drenched Florentine morning, I found time to set off in search of a unique library I’d wanted to visit for years. Starting out at the Ponte a San Niccolo, a bridge spanning the Arno River, I meandered through the ancient streets for a couple of kilometres until I reached my destination.

The Laurentian Library, also known as the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenzia (and the library Michelangelo designed), is adjacent to the Basilica di San Lorenzo, which is the second largest church in Florence.

When I arrived at the Brunelleschi courtyard it was bathed in soft, muted light and carpeted in velvet green grass. Nuns coming and going through small brown doors were mostly silent or whispering to each other.

Then a window was pushed heavenward and a smiling nun began selling tickets to visit the library Michelangelo designed.

After securing my admission, I walked up some plain wooden stairs to the entrance of the library. It was an unremarkable door in the corner on the first floor and it provided no clue about the incalculable treasure behind it. I might have been walking into a storeroom.

Michelangelo's David

On my last visit to Florence, I’d stood at the feet of Michelangelo’s David in the Accademia Gallery and couldn’t find any words.

Weighing more than 560 kilograms and standing almost 14 feet tall, David is carved from a single block of white marble.

Michelangelo had a deep knowledge of human anatomy, and he acquired this skill from participating in public dissections.

As a young teenager he joined the court of Lorenzo de’ Medici and became acquainted with the physician–philosopher members there. It wouldn’t have surprised anybody that by the age of 18, he was performing his own dissections.

The pulsing veins on the back of David’s hands are testament to Michaelangelo’s understanding of anatomy. So are the flexed muscles juxtaposed against David’s beautifully contoured limbs.

In 1501, when Michelangelo began to carve David, he was only 26 years old.

Over the next three years he worked in secret, often at the expense of his health.

His biographer, Ascanio Condivi, wrote that Michelangelo barely ate during this time. He snatched brief naps while fully clothed between bouts of work.

Finally, on 14 May 1504, David was ready to be moved to his first home, the Piazza della Signoria. And it took 40 men to push the statue there on a large wooden cart.

The beginning of the library Michelangelo designed

A lauded architect, painter and sculptor, it wasn’t until 19 years later that Michelangelo began sketching the design of the Laurentian Library.

Construction began on the library in 1524, and continued until he left Florence for Rome in 1534.

After his departure, Michelangelo’s followers – Medici court artist Giorgio Vasari and Bartolommeo Ammannati – continued with the construction of the library. They based their work on plans and verbal instructions from Michelangelo.

The library designed by Michelangelo was finally opened in 1571. It was 37 years after Michelangelo left Florence and seven years after his death.

Michelangelo's staircase to heaven

The vestibule, or entrance hall, of the library is almost overtaken by a colossal staircase. It’s composed of three adjoining flights that ascend to the library.

Built by Ammannati in 1559, he used a clay model created by Michelangelo as a guide.

The staircase design is said to have come to Michelangelo in a dream. The three flights of stairs are composed of smooth grey sandstone and plaster, and the centre flight is convex with three complete elliptical steps at the base.

On exiting the library, the steps look like lava waiting to float you down to the level below. It’s a remarkable effect and characteristic of Mannerist (or Late Renaissance) architecture for which Michelangelo is well known.

The purpose of the library

Michelangelo designed the Laurentian Library for Medici Pope Clemente VII. The library’s purpose was to store 11,000 manuscripts and 4,500 early printed books collected by Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent.

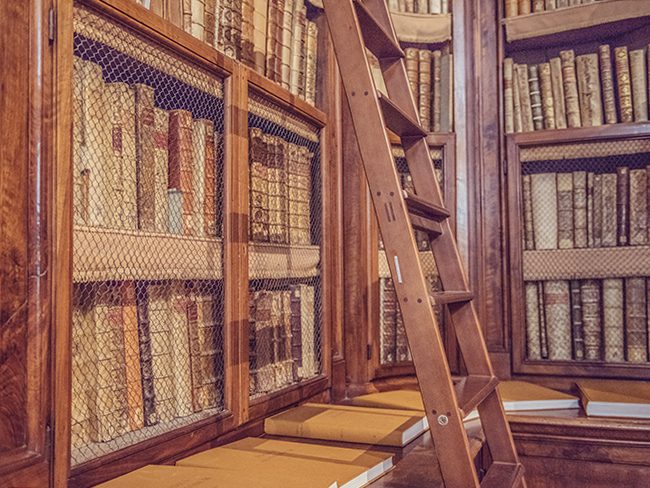

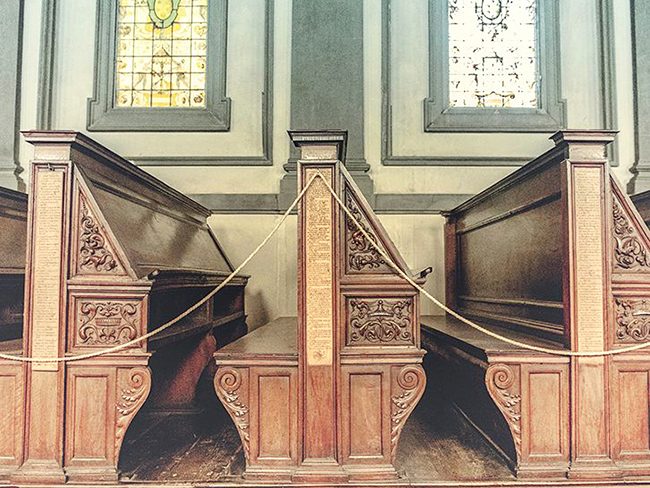

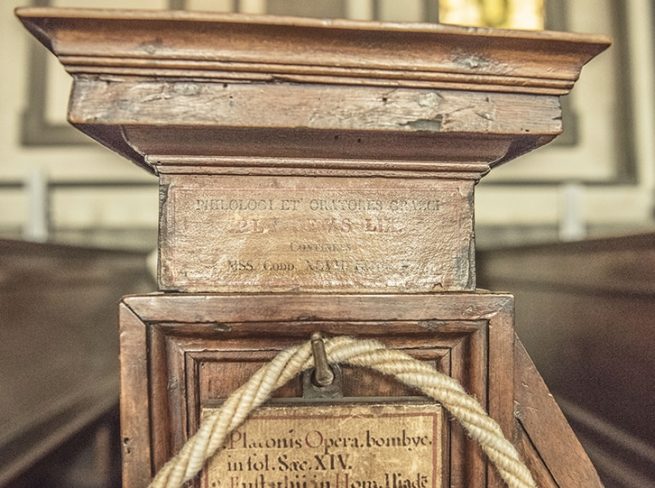

It’s considered to be one of the most valuable collections of ancient manuscripts in the world. Manuscripts and books were organised by subject, and a panel attached to each lectern displayed a table of contents that are read from the centre aisle.

The books and manuscripts lay on shelves built into the lectern, while a sloping platform allowed the reader to position their reading material.

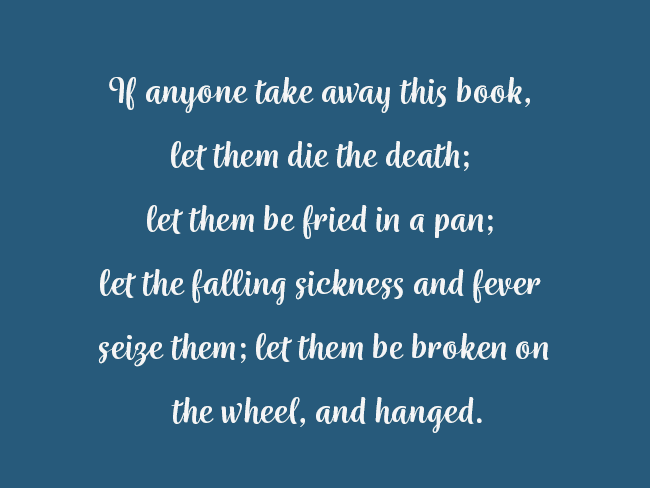

The Laurentian Library was a chained library, which was a common feature of public libraries in the Middle Ages when books were scarce and valuable.

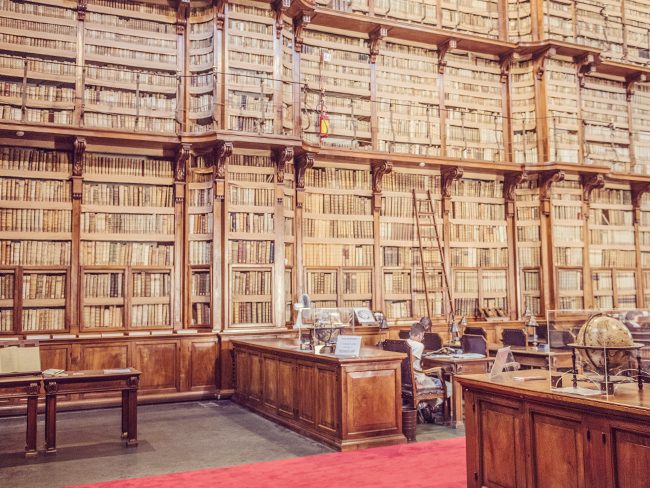

It’s long rectangular reading room has simple well-defined lines. The reading desks, which sit effortlessly in ordered rows, are set off by ancient red and white terracotta floor tiles that reflect the rust-coloured tones of the timber. All of this is complemented by stained glass windows that run the length of the reading room on both sides.

The linden wood ceiling is glorious. It was carved between 1548–1550, using early drawings by Michelangelo. And the entire space is transformed into a visual tapestry of familiar rustic tones when warm sunlight streams through the windows.

These superb architectural elements blend so harmoniously with the practical seating and reading arrangements that you feel as if you’re in a great cathedral.

Rare and ancient manuscripts

Among the ancient and rare manuscripts in the Laurentian Library collection are Tacitus, Pliny, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Quintilian.

The Codex of Vergil is also there, along with the oldest extant copy of Justinian’s Corpus Iuris Civilis.

One of the most fascinating acquisitions is an early complete collection of Plato’s dialogues. It’s one of only three in existence.

The library Michelangelo designed is now owned by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. Unfortunately, it’s open only on selected weekdays.

Don’t expect to see crowds of visitors, as this is a place of study and research. The library encourages conservation and study of its manuscript and rare book collection.

If you manage to find your way to Michelangelo’s library, it will stay with you long after you leave the warmth of the Brunelleschi cloister.

Take a tour of the Laurentian Library in Florence.

Smarthistory (2011). Laurentian Library.

How to find the library Michelangelo designed in Florence.

Before you go read this ...

If you love ancient libraries, you might also like to read Searching for Rome’s oldest public library.

If you want to travel slowly, savour the moments and connect with locals, check out How to have a slow travel experience.

And if you’re keen to write about authentic slow travel jump into my Slow travel writing tips and experiences.

About Sharon Lapkin

Sharon is a content writer and award-winning editor. After acquiring two masters degrees (one in education and one in editing and comms) she worked in the publishing industry for more than 12 years. A number of major publishing accomplishments came her way, including the eighth edition of Cookery the Australian Way (more than a million copies sold across its eight editions), before she moved into the busy world of corporate publishing.

Sharon worked in senior roles in medical colleges and educational organisations until 2017. Then she left her role as editorial services manager for the corporate arm of a university and founded Textshop Content – a content writing and copyediting agency that provides services to Australia’s leading universities and companies.